Now that we have found ourselves here, what can we do to get back on course? But before I try to answer this question the best way I can, let’s deconstruct the upshot the pandemic left in its trail.

As expected, a lot of research has shed light on the growing effect of COVID-19 on learners all around the world; whether short-term or long-term effects but it is alarming to note that not many of these studies have focused on students ages 5 and below. Given that these younglings will by this time only have acquired the adequate communicative abilities to request food and play and other things alike in between, what indicators are there to let policymakers know the needs they have when it comes to their learning, other than when said prescribed learning begins to show its effectiveness or non-effectiveness – which may be visible during or after this learning stage. When it comes to this aspect, they usually have no say in how they want to learn until they begin to show their teachers if the learning was productive or counterproductive and this is largely due to the fact that their language for expressing intricate needs such as these, has not yet been developed.

In trying to fill the gap of little to no empirical research that zeroes in on monitoring the knowledge gap of students from kindergarten to the end of primary school, from a longitudinal perspective in the domains of mathematics, English and science, Gyöngyvér Molnár and Zoltán Hermann, authors of “Short- and long-term effects of COVID-related kindergarten and school closures on first- to eighth-grade students’ school readiness skills and mathematics, reading and science learning, Learning and Instruction, Volume 83”, used pre-pandemic achievement data as benchmark indicators in their study and came to the denouement that students who started school in 2020 and 2021 were differently skilled on average than students who started pre-pandemic due to the lack of explicit in-person training as numeracy and reading skills because of the number of school days lost for their sample in Hungary.

From my personal point of view as a maths teacher, I can attest to this being a parallel for those in primary and secondary schools too. When I would eventually meet my students in the classroom after the lockdown was lifted, I came to the conclusion that I achieved little to nothing during the months of online instruction particularly because we were starting a new school year in the wake of the lift – let’s not even talk about the amount of work put into adjusting their minds to in-person learning from online learning.

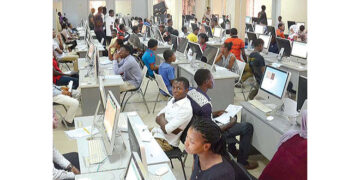

Because statistics are difficult to come by in Nigeria, we can make inferences from the survey conducted by Chen et al (March 2021) in the top OECD nations including China to give us an idea of what must have happened in our nation. Only a third of the respondents viewed online learning as nearly successful as in-person learning while two percent of those respondents from Japan thought it was equal to online learning, and the other ninety-eight percent thought it was the absolute worst. As classes continued online in these nations, teachers saw the efficiency of instruction decline. The same survey recorded that learning and instruction in private and wealthy schools were more effective as most of their students had access to technological facilities and were usually tech-savvy. I am sure by now you are beginning to get a clear picture of what happened in Nigeria as more than 39 million learners had their learning disrupted. In another twenty years or so from now, these individuals will represent a major part of the nation’s labour force and in turn the nation’s economic output. This is not to say that there weren’t significant efforts made by policymakers in Nigeria like those in Edo and Ogun states. And this is not also to be a prophet of doom as we can see that criteria for work and career growth are beginning to take a new turn. However, the skills lost are still very much required for the future of work and we need to find ways to ensure that they are taught and learnt.

To move forward we must therefore come to the realization that how we used to learn before COVID is still as important and productive but with the agency of technology it can be more effective. Thankfully, in Nigeria today, access to the internet has increased and is becoming a bit more affordable but might not be affordable on a large scale for our public primary and secondary schools, therefore, the tool for technology must fit into our context particularly because of the environment most of our learners live and grow in. Taking a cue from the ‘OGUN DIGICLASS’, more television and radio programs that cover reasoning, fluency, competence and understanding in mathematics, science and English should be funded by the Ministry of Education at both federal and state levels. The feedback system from this program can also be a prototype for measuring the effectiveness of such programs.

The Nigerian curriculum needs to be fully transmitted from paper to the walls of the classroom and then consolidated. While there has been a growing body calling for the entire overhaul of the nation’s curriculum, it’s imperative to critically look at what those who learnt with the curriculum are achieving all around the world and what needs to be added or removed to help our learners do better. By consolidating our curriculum, we can expect that full recovery from learning loss can almost be achieved. Once educators and policymakers can through research determine which skills, knowledge and competencies should be set as priorities for each grade level, they can go ahead to ensure that materials and the time required are included in the day-to-day learning of students. A simple way to do this is, for example, by asking primary 5 students to get primary 4 textbooks and assign homework from this textbook during the holidays or weekends. This will help as both diagnostic and consolidating measures.

Policymakers should consider extending school days to increase the time spent on instruction so as to improve learning outcomes. In Kenya for example, the government announced a two-year accelerated crash program that adds a fourth term to the regular three-term school year. Mexico also planned extensions to the academic calendar which was announced by the Ministry of Public Education. We can find several policies across the world like this that can be adapted to fit our context.

Consequently, the government needs to up its funding game for educators and researchers. That’s as succinctly put as it can be. Infrastructure, teachers and learning materials must be heavily invested in because these are usually easy motivators for teaching and learning. The government needs to help improve the skills and competencies of its teachers as there will be no recovery without professional development and support for teachers. Also, the need for data to adopt best practices in education is important. Independent researchers should be accommodated in order to help shed light on issues that require immediate attention from the government.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.