Tell us who Dr Dahiru Sani is. What were your growing up years like?

It is indeed an honour and a pleasure to be invited for this interview. Let me put it this way, your reputation as a well regarded education focused magazine actually precedes you. And going by the past copies of EduTimes Africa that I have seen, I really am lifted by your work. So, for Dhahiru Sani to be associated with this wonderful initiative is a huge step for me.

Dhahiru Sani is a young man who was born sometime in the late 60s. Early life was in Kaduna as I was also born here in Kaduna State. I had the privilege of being born into a family of intellectuals. My dad was a catering and hospitality expert, and he could be credited as being one of those who brought hospitality and tourism technology from Italy, from the U.S. and from Britain into northern Nigeria. So, he was one of the earliest Nigerians involved in growing chains of hotels, 5 Star hotels, at a time when foreign investors identified Nigeria and northern Nigeria in particular as a hub for tourism. So, this is what kind of shaped my early life as it afforded me the opportunity of visiting quite a lot of those countries early in life, while traveling with my father or with the family. It gave me several unique opportunities. For instance, I speak French quite fluently. Certainly, my early years and my upbringing helped to shape my worldview. Primary school was at Kaduna Capital School followed by secondary school at the Federal Government College, Kaduna, which in those days was top notch. University education was at Ahmadu Bello University also in Kaduna, where I bagged my Bachelor’s in business, specializing in finance. Again, I specialized in stock investment securities for my MBA and eventually went into derivative markets in my PhD at Switzerland’s pioneering business school, the Swiss Management Centre.

Also, I’m currently running another doctoral program, focusing on developing finance because I’m also beginning to see that where the challenge is going to be for Africa in the next 10 years will be on how to manage the current epidemic of debt. So, this is me in a nutshell but as we continue our conversation, I’m sure you will learn more.

What are your likes or dislikes?

Yes, this is a beautiful question. I think my dislikes essentially are when I see people who don’t strive. Let me start from that perspective. When I see people who are entitled, when I see laziness, when I see people who are not connected to intellectual reasoning and don’t have value. Those who seem to be ignorant of the fact that you have to give something to your brain in order for it to produce something. I really dislike all those sorts of things. What I really, really love, and I must confess this to you, first and foremost, is love. I mean, I’m obsessed with love. I think love is the biggest power that God has given us in this universe. And secondly, I am really into innovation. I want you to be able to tell me that this is A, but I can put it this way, it can be A, it can be R, it can be Er, you know. I like people seeing things from different angles, different perspectives. Anything at all, anything being done, anything being thought, anything being created, I want you to be able to tell me that we can do it this way, we can do it better. There’s never a best for me, it’s always about how you are able to iterate.

And I think that is really what drives advancement at the end of the day.

As an individual who has attained the very highest level educationally in addition to having several professional certifications under your belt, what recommendations would you make to strengthen Nigeria’s education system?

Another great question. Let me start by giving this a bit of a historical perspective. Where is the educational system coming from? Okay. So, the educational system in Nigeria from primary to tertiary, if you look at the entire value chain of production of people who we call, quote and unquote, educated, is still suffering from the original design of service and not innovation. The British bequeathed to us an educational system that’s quite good, but embedded in that educational system is a focus to maintain a specific type of status quo, to maintain the institutions they created, to support the intentions of the colonial masters.

That’s why you see that we are still very steeped in what I call the pedagogistic elements of education. Meaning, seeing every learner as a baby, every learner as a child. Our educational system has not evolved to a point where you give independence to learners as they individuate. In psychology, that’s what they call separation, individuation. Meaning that from zero to 18, zero to 15, you know – it’s just like the process and metamorphosis that a butterfly goes through – so with each stage of that metamorphosis, the methodology for educating people has to change. But regrettably, our educational system is still tied, heavily tied to that notion of, I know it all, I’m the professor, I’ll teach you, I’ll hand the information to you, cram it and return it to me. That’s how we still perceive education. And I think that’s one of the fundamental drawbacks. The second drawback is really the manufacturing, the essence. Today, it has turned to what we call manufacturing of certificates. We’re not producing graduates. We have institutions and a value chain which produces a certificate rather than an individual. When I say an individual, I’m talking about somebody who can stand his own. I have a Bachelor’s of Science in Agriculture, so to that extent, I should be able to facilitate any agricultural intervention from end to end. I have a Master’s therefore I should be able to create a new approach to agricultural practices in my country. I have a PhD, so I should be able to in fact develop theories that should serve the purpose of future agricultural arrangements, agricultural projects, agricultural ideas in my country and the world over. As I have a PhD, I should even be able to stand my own and do things that will make people outside of my country look at my continent and say, yes, there’s something that comes out of this continent. How you can understand this is by just asking these simple questions. During your time at school, how many textbooks were written by Africans? How many textbooks that you used were written by Nigerians or Africans? How many textbooks came out of this continent? How many of all those lofty economic theories that we use, from my professional perspective – the finance theories that shape our eventual graduation – how many of them came out of the continent? So if you look at the fundamentals of our educational systems, it’s all like that. So, if somebody is to design an educational system, he should design an educational system in the light of his own challenges. If you are going to follow someone else’s educational system, you are only going to fall in line, so that you become an agent of solving that person’s problems. If you look at economics, for example, from Ricardo to Keynes, they were all challenged by scarcity. So the basis of the economics that they were teaching or they were professing, which we have all come to accept as the standard today, is that resources are scarce, and that has become our mentality. But in Africa, resources are abundant. So the economics that should drive our own thought process is the harnessing or the management of abundance rather than looking at it from a perspective of scarce resources. Look at Nigeria for example. Just take Nigeria, forget about Congo, forget about Sierra Leone, forget about the gold fields in South Africa. The entire continent is brimming with an abundance of natural resources. This means the basis of the economics we practice in Africa is flawed. That’s why the continent is suffering. The knowledge is based on people who didn’t have resources. They have winter, they have this, they have that and for the whole year, it’s scarcity. So that’s why they became explorers and they now develop theories that actually help them to do what? Explore. That can help them to undermine, that can help them to recalibrate arrangements, which they refer to as in quote and unquote, capitalism, maximization of profits, and so on and so forth. In our own case, it’s not that way. So, we have to wake up as a continent, as Nigerians, because we actually are the leaders of this continent, and say, hey, wait a minute. We can look at this in another way. And our academics can come up and say, okay, let us develop another theory, given our abundance. And it becomes an ‘Adebiyi’ theory of economics for example, and they test it, validate it, and sell it. It is at that point in time that our educational system will begin to liberate this continent. We have a responsibility to rethink our educational system from primary to tertiary, from our own perspective, from our own challenges, from our own abundance, from our own cultural understanding. I’ll give an example. Do you know how many engineers, how many medical doctors, how many environmental design experts we have lost in this country simply because we insist they must all speak English? When I went to China, they were not speaking English. All the transactions I did in China were computed on my mobile phone. I just have the number, they see it, we agree. And they were experts. I’ve seen Chinese doctors, they don’t speak English. I’ve seen Chinese engineers, they don’t speak English. I’ve seen Russian engineers, they don’t speak English. What is this obsession with the English language? Why must I score A1 or C4 in English before I get into a tertiary institution? It’s totally unnecessary. Start with a few disciplines, for example, and say, look, these disciplines have been localized. If you’re Yoruba, we are going to teach in the Yoruba language. We’re not saying all disciplines, but start with a few. Let us offer that local language option. There are so many children out there who are lost, but they are very sound, very sound. But simply because they never had the opportunity to learn English, they are disenfranchised and never amount to anything. These are the bandits today. They are the bandits because they were educationally excluded, just because of the insistence that they must speak English before they can get an education. No, every language is a language. Every language has a right to evolve into translation of a discipline for people to understand it within the context of their environment. So, these are some of the things and realities that we have to face as a country, as a continent. For instance, if there is a medical doctor in the hinterlands of Jigawa State, what does he need English for? Who is he speaking English to? His job is to treat the children, treat the mothers, treat the elderly and they don’t speak English there. If you go deep into Ondo land, the dialect that they speak there will complicate your life. Yes, they speak a bit of English, but still, the man who is going to speak to the doctor, for example, is better able to explain what is wrong with him from his local language perspective. Imagine interfacing with medicine that is understood from that perspective. It will make a difference. So this educational exclusion, because of language barrier, is a big, massive dent on our future, a massive dent on our future, which we have to change. They say to get into university, you must pass English, you must pass mathematics. It’s nonsense. And then now they say before we can relocate abroad, we must pass IELTS. Why don’t we insist that before any European or foreigner can come to work in Nigeria they must pass at least Yoruba IELTS, or Hausa IELTS, or Igbo IELTS, and then we charge them for it as well? Yes now, reciprocity. If a foreigner wants to do an NGO project in Maiduguri, he or she must pass a Hausa language test. Until we begin to do things like this, we will not be seen as a serious set of people.

What led you to establish the Kaduna Business School back in 2004 and is it a degree awarding institution?

Kaduna Business School is not a degree-awarding institution. Originally, we set out purely to service executives. We actually patent our work. I originally was a banker. I worked at a few banks and then I left because I saw a pain. The pain I saw was that the quality of people that were employed, even within the banking space, were not strong enough to deliver the kind of value we wanted to deliver within the banking system. I now saw that, yes, the graduates would come out of university, but in terms of their ability to man the responsibility, there were still several gaps. So I said, no problem, even within the banking system, I set up my own evening lessons. I would bring all my boys and girls together and teach them cash flows, teach them cash to cash cycle, how to lend effectively, how to recover effectively, all those things that you ought to know as a banker, because they really were not training them in these things from the university. Not even those who read banking and finance or whatever. And then again, we were employing anybody who had a 2.1 Degree and who could speak very well. But you still need to understand finance to be able to serve as a banker. So after some time, I just knew that this was not my calling. Sitting down behind the desk and giving credit is not my calling. My calling really is to go out there and make a difference. So we started out as an executive education institution. Executive education essentially means that we are concerned with the work people are doing. Our interventions have to do with finance. How can it be better? What are the gaps? If you are looking at the market, looking at the human resources, how do you do it better? The whole idea was to interface business to business, work with those businesses, see their challenges, and then create another intervention that services and helps the businesses. But as time went on, of course things also evolved. But still, the approach is not to rush and become a university. There are enough universities already. What was needed was to create a programme that’s innovative enough, so that even after young graduates have finished, they can still come here, run a programme that can help them with job creation, that can help them with innovation, that can help them make sense of their discipline. We joined hands with the National Board for Technical Education, and we created a kind of institution called Innovation Enterprise Institution. So, an Innovation Enterprise Institution is the kind of institution that actually does not go the conventional way, but goes the innovative way and creates interventions or programmes that you won’t find in schools. Programmes that you can pursue directly as a youth and you can also come directly from having graduated. We then started looking at things like entrepreneurship specific, artificial intelligence specific, market access specific, opportunity screening specific, so that you can actually come and specialize in these areas and get a diploma out of it. Then you can now make sense out of your discipline. Therefore, somebody who read biochemistry and could not make sense out of their biochemistry, rather than thinking of taking their certificate and going to use it as a teacher, by the time he goes into our Innovation Enterprise programme, he will begin to see that same biochemistry from an entrepreneurial perspective. The historian, rather than thinking of going to a secondary school to become a history teacher, can begin to see how he can use technology to advance history. With the realisation that history is critical to our lives, he can use technology to commercialize history. Many researchers who have concluded their research can go through our programmes and discover how they can commercialize their research. Research is not supposed to be dumped on the shelves of libraries. They are supposed to help humanity. But if we don’t create programmes that help to unlock that process, then we will just be playing the ostrich. So that’s how we operate as a business school.

So how is KBS, located in the centre of learning in Nigeria; Kaduna State, planning to intervene in the number of out-of-school children in Northern Nigeria, and thereby help to transform their education to economic and business skills in the future?

Fantastic. In terms of out-of-school children, during the El-Rufai administration, we were part of some interesting conversations with some agencies, and I remember very clearly that it led to the establishment of the Edu-Marshalls in Kaduna State. The Edu-Marshalls are people who are employed to keep going round the city, keep going round the local governments and any child that is seen floating around is picked up. We then get the data of the parents, identify the local government that is closest in proximity to where the child lives, and then the child is plugged into an educational programme for free. But beyond that, we are actually also looking at out-of-school children mapping. We are trying to work with some donor agencies to see how we can really map the number of out-of-school children within the local governments in Kaduna State, for example. But then the real challenge is how to create programmes and build capacity within the primary educational system, that is not just primary one to six or primary one to seven, but has programmes within the primary educational system that also speaks to certain children that may have crossed a certain age. For instance, some may have been out of school until the age of 14. You can’t bring such a child back to Primary one. So, how do you create a programme that is skill-based, which then absorbs him into a vocation so he can become useful to himself and society, but achieving this within the primary school system and within the secondary school system? That is the way to go. But what we have currently is still just the traditional route. In a situation where the child is already 12 or 13 years old before he commences school, if he follows the conventional route, he will quickly become disenchanted and will dump it because school will not excite him. So, we must have a special intervention because when you are talking about out-of-school children, education from the white man’s perspective is an incremental process. Meaning, there are certain things that if you didn’t do it in year one, year two, year three, year four or year five, you can’t just jump in, in the middle. But innate ability is always there and that can be harnessed. If you gather a bunch of out-of-school children and we try to sort them from the point of view of what their calling is, the sort of things that they like to do, some will tell you, oh they want to weave, some will tell you that they would like to do herbal medicine because they saw their grandfather doing it while some others will tell you something else. By the time we aggregate, we will understand how we can now plant programmes within the primary and secondary schools, where some of these out-of-school children can go and pursue these kinds of programmes that will push them into life with a skill. So our thinking is a little bit different because it has also evolved from just catching them and throwing them into school, which is what we’ve been doing in Kaduna State. Right now we are working assiduously towards a kind of intervention that really secures them from their own nuanced understanding, so we interview them, show them that we are genuinely interested in their welfare and future by considering their age, looking at their calling, looking at their preferences and then trying to mount those kind of programmes within primary and secondary schools to help them. In China today, you will see that children at very young ages can learn tailoring, can learn catering, can learn all sorts of things. That’s really what’s guiding our thought process and maybe by the end of the year we should be able to have something out for validation.

You can read the concluding part of this exclusive interview in our June issue.

_______________________

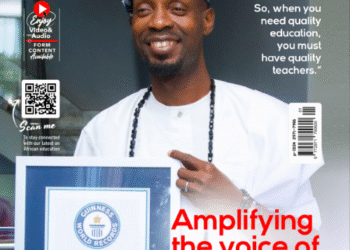

Dahiru Sani, PhD

A Visionary Leader in Business Development, and Innovation

Dr. Dahiru Sani brings a wealth of expertise and a distinguished track record in the realms of finance, business development, and education. As an associate of the Chartered Institute of Stockbroker, his academic journey is underpinned by a commitment to excellence and a robust set of professional certifications.

In 2003, Dr. Sani emerged as a visionary leader, founding the Kaduna Business School (KBS). In this pioneering role, he played a pivotal part in its growth, accreditation, and establishment as a beacon of corporate education in Nigeria. Serving as the Founder and Chair of the faculty, Dr. Sani not only successfully led fundraising efforts but also provided external leadership, transforming KBS into a thriving institution.

His strategic acumen continued to shine as the Vice President of Business Development (Africa) at Transcontinental University, Dublin, Ohio, USA, from 2019. Dr. Sani has been instrumental in developing growth strategies, identifying new markets, and fostering crucial corporate client relationships.

From 2016 to 2018, Dr. Sani served as an Embedded Economic Adviser for the Kaduna State Government/World Bank. During this period, he made significant contributions to the establishment of an Economic strategy framework within the Intelligence Unit of the Budget and Planning Ministry, contributing to the economic vision of Kaduna State.

Dr. Sani’s impactful journey in the banking sector includes a senior leadership role at Continental Trust Bank, now merged with the United Bank for Africa. Here, he directed branch management efforts, overseeing strategic growth with remarkable success. As a Senior Business Development Manager at FSB International Bank, now Merged with Fidelity Bank, he further showcased his prowess in retail banking, relationship management, and credit risk management.

Throughout his illustrious career, Dr. Sani has undertaken comprehensive consulting projects with prestigious organizations such as the World Bank and the Department for International Development. Among his notable achievements is the implementation of a first class 5,000 Youth Enterprise Development Programme in partnership with the Bank of Industry. Additionally, his strategic leadership played a pivotal role in expanding the United Bank for Africa in Northern Nigeria as a regional manager.

Dr. Sani’s commitment to the financial industry is underscored by his successful completion of various professional development programs and certifications. As an Accredited Business Development Service Trainer and an ACS-certified member, he continuously seeks excellence in his field.

In his pursuit of excellence, Dr. Sani has engaged in various ad-hoc assignments, including serving as a Member of the Council for the Accreditation and Certification of Business Development Service Providers in Nigeria and contributing to the Financial Inclusion Community of Practice.

With a strategic vision, unparalleled leadership experience, and an unwavering dedication to excellence, Dr. Dahiru Sani is poised to make a substantial contribution to the success of any institution fortunate enough to benefit from his expertise

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.