One of the greatest challenges facing educators today is generative artificial intelligence (AI) and its ability to accurately and efficiently complete student assessments. Educators, policymakers, and parents alike have been globally debating the role that generative AI should play in our children’s education. On one side of the debate, policy makers in Italy have decided to completely ban AI in schools, while other nations have decided to adopt a more laissez faire approach. In order to make informed decisions about how to regulate students’ use of AI, it is imperative to understand the relationship between generative AI and students’ learning.

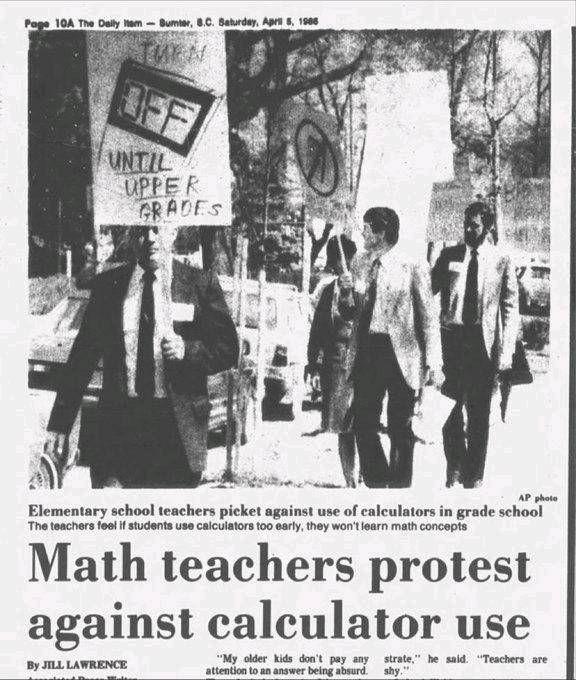

When engaging in debates around the impact of generative AI on education, you often hear the analogy that AI is just like a calculator was for math education. Current researchers in the field of AI and education have recently published an article pushing back against this very analogy. Lodge and his colleagues (2023) in their research article argue that the analogy of the calculator simplifies the complexity of generative AI and instead argue that it is more similar to the invention of electricity. With the invention of electricity came a complete shift in technological infrastructure. So, what does this mean for us educators?

Lodge and his colleagues (2023) in their article address a new conceptual model for understanding generative AI and its impact on student learning. The four components are cognitive offloading, extended mind, co-regulator of learning, and hybrid learning. In this article we will explore the component of cognitive offloading and provide practical examples for educators on how to implement them into their instructional practice and assessment design.

Cognitive offloading occurs when a student relies on technology, peers, and other resources to reduce the mental effort that is required for a task. This can allow students to delegate lower order thinking tasks to technology, while freeing up cognitive space for them to engage in higher order thinking and complex-problem solving.

Therefore as an educator you need to identify the key areas in the curriculum that students must be able to learn and demonstrate on their own. You must also identify the areas which they can cognitively offload to generative AI. It is vital that you are explicit with students about the rationale for why you are not allowing them to use generative AI for a certain cognitive task. When it comes to writing, it is crucial that students practice the pertinent skills of sentence formation, syntax, and forming coherent arguments. These are cognitive tasks that should not be offloaded to AI, but should instead be the responsibility of the student. As the student practices these writing skills, they form stronger connections in the neurons of the brain.

While there are many skills that students benefit from cognitive struggles there are also many situations where cognitively offloading the task to generative AI will not negatively impact the student’s learning. For example, with writing tasks, students can use generative AI to provide them with critical feedback that they can use to improve their writing. This allows students to critique their work via generative AI and to then use the higher order thinking skill of applying the feedback and reflecting on how they incorporated the feedback in an effective way. In this example it is beneficial to student learning to offload the cognitive skill of writing feedback to generative AI.

Educators play a pivotal role in developing students into self-regulated learners. For students to develop these critical thinking skills, educators must provide students with explicit instruction and model how to use generative AI in an ethical and effective manner. A simple way to ensure there is transparency is to produce a rubric that outlines for students where they are allowed to use generative AI and tasks that are forbidden to use generative AI. For example, for an assessment, students might be provided with a rubric that explicitly states they can use generative AI for ideation and brainstorming, but they are restricted from using generative AI to write their report. The more explicit the educator is with the student, the stronger the learning outcome.

Teachers must model for students the appropriate ways in which they can engage with generative AI and must be aware of pitfalls that students might encounter. While I was conducting an observation of a secondary teacher, I was impressed that she added the use of generative AI into her lesson plan. As part of her formative assessment she was asking students to write what they knew about a specific topic (tapping into the students’ prior knowledge) and then asking them to prompt ChatGPT to come up with a response. She wanted the students to use ChatGPT as a way to build on their previous knowledge. In a class of more than 25 students, not a single student wrote their own ideas, instead they automatically went to ChatGPT and prompted it to respond. They all unanimously cognitively offloaded the task to generative AI. When I walked around the room and engaged in conversations with the students, they informed me that they did not know anything about the topic and therefore had to rely completely on ChatGPT for a response. This is an example of where teachers need to scaffold the task for the students. My recommendation to the teacher was to have the students complete the prior knowledge task prior to allowing them to engage with ChatGPT.

Students need to be provided with clear instructions and guidelines to ensure that they are not cognitively offloading tasks that they should be doing on their own. Educators, I call on you to take on the heavy responsibility of preparing students to engage with these ever changing technologies and to ensure that students are aware of the benefits and challenges of using generative AI when cognitively offloading tasks.

Reference

Jason M. Lodge, Suijing Yang, Leon Furze & Phillip Dawson (2023) It’s not like a calculator, so

what is the relationship between learners and generative artificial intelligence?, Learning: Research and Practice, 9:2, 117-124, DOI: 10.1080/23735082.2023.2261106.

_______________________________ Stephanie Martin Hailing from South Africa and Australia, Stephanie is the co-founder of Edvance Education Consultants and has over 10 years of experience as an educator and thought leader in the education profession - both in Australian and international school systems. As an educator in universities and schools, Stephanie focuses on building and sustaining high quality pedagogical practices to enhance teaching and learning, as well assisting organisations to implement assessment methods that foster 21st century skills. Stephanie is a published co-author, researcher and a dynamic keynote speaker. Dr Afnan Boutrid Dr Afnan Boutrid (Ed.D), an AlgerianAmerican is the co-founder of Edvance Education Consultants and a practising Assistant Professor in academia with a wealth of experience in the education profession, both in the United States and Middle East region. Afnan specialises in curriculum design, assessment and culturally responsive teaching practices and is an active researcher, lead author and lecturer in Dubai, UAE. As a thriving researcher, Afnan believes in the power of bridging the gap between theory and practice, ultimately bringing change and empowerment to the field of education. @edvanceconsultants info@edvanceconsultants.com.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.