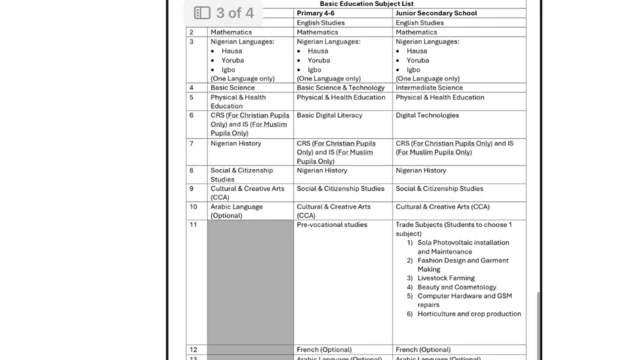

“Digital literacy and basic entrepreneurship will now be compulsory at the junior secondary level. Coding and robotics have also been introduced as foundational courses to expose pupils early to technology-enabled problem-solving.” — Federal Ministry of Education

Nigeria’s latest reform of the national curriculum reducing the number of subjects in primary and secondary schools, integrating content areas, and introducing new priorities such as digital literacy and trade subjects has been met with both relief and cautious optimism.

At first glance, it seems a long-overdue step towards easing the academic burden on learners and teachers, while also aligning education with the realities of a changing world.

Yet, as with all reforms, the details of implementation will determine whether this shift becomes a milestone or another missed opportunity.

For years, education stakeholders have complained about the excessive number of subjects Nigerian pupils are expected to take.

Children as young as primary school pupils were being taught as though preparing for postgraduate studies. Teachers struggled to spread themselves thinly across topics, while learners often found themselves overwhelmed, memorising rather than mastering.

In this light, the decision to streamline the curriculum by integrating stand-alone subjects is welcome. It reflects a global best practice of clustering knowledge areas rather than scattering them, allowing more depth in fewer domains.

The introduction of digital literacy is particularly significant. In an economy increasingly driven by technology, coding, artificial intelligence, and digital communication, preparing pupils for a digitally enabled world is no longer optional.

Likewise, the inclusion of trade subjects in secondary schools signals a recognition that education must open multiple pathways, not only towards university but also towards entrepreneurship, technical expertise, and employment in skilled trades.

These additions respond to Nigeria’s urgent need for a workforce that is not just certificated but competent.

However, reducing the number of subjects is not the same as reducing the challenge of education. Real reform requires aligning curriculum change with resources, teacher preparation, and assessment systems.

If teachers are not trained to integrate content, if lesson plans remain abstract, or if textbooks lag behind the new design, then the reform will remain cosmetic.

Curriculum is not merely a list of subjects; it is a living framework that shapes teaching, learning, and assessment in classrooms. Without robust investment in pedagogy, professional development, and infrastructure, the reforms risk being only a policy headline.

There are also critical omissions. While Digital Literacy is included, the new subject list appears silent on Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) – a domain increasingly recognised as essential for holistic child development. Equally concerning is the absence of explicit Financial Literacy.

In a country where economic insecurity is widespread, teaching young people how to manage money, plan savings, and understand the economy is a life skill as important as mathematics or science.

Were these topics integrated into other subjects, or were they simply overlooked? Clarity is needed.

At the senior secondary level, the reforms should go further by embedding true multi-exit pathways. Not every learner needs to pass through the narrow gate of university admission.

Strong vocational tracks, tied to industry partnerships, apprenticeships, and government-backed skills centres, would give learners both dignity and employability.

This requires more than curriculum adjustment; it demands serious investment in technical education and a cultural shift towards valuing diverse routes to success.

Perhaps the loudest alarm remains the literacy crisis. A troubling proportion of Nigerian pupils, even at secondary school, still struggle with reading, writing, and basic arithmetic.

Reducing subjects could free up classroom time, but will that time be redirected towards foundational skills? Unless reforms address this emergency, Nigeria risks producing students who move through school without acquiring the core competencies needed for citizenship, employment, or lifelong learning.

Ultimately, the measure of success will not be the neatness of the subject list but the lived reality of pupils in classrooms.

Will they leave school able to think critically, solve problems, communicate effectively, and adapt to a fast-changing world? Will teachers be equipped and supported to deliver the curriculum in meaningful ways? Will government provide the resources and political will to sustain the change?

This reform marks progress, but progress is not the same as success. Stakeholders must hold government accountable, ensuring that curriculum reform does not end at policy pronouncements but translates into improved outcomes for every Nigerian child.

For now, the streamlined curriculum offers a hopeful opening, the success lies ahead.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.