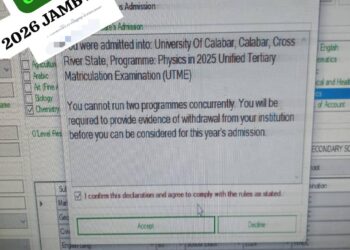

For many Nigerian students, this conversation isn’t really about culture — it’s about exams, results, and what gives them a fair shot.

Following widespread reactions to its language policy shift, the Federal Government has clarified that indigenous languages have not been banned in schools. Instead, their use as the main language of instruction has been limited to help students cope better with national examinations conducted in English.

Speaking on ARISE News on Sunday, Minister of Education, Dr Tunji Alausa, said the policy rethink was based on how students were performing across different regions.

“Now, we’ve not banned the use of indigenous language in school. What we’ve done is a SWOT analysis of what’s happening,” he said.

Alausa acknowledged that children often learn faster when taught in their mother tongue, especially at early stages, but noted that Nigeria’s diversity makes nationwide application complex.

“We have to look at a multi-ethnic society, a multi-linguistic society. Today, we have 646 languages in this country,” he said.

To ease fears of cultural erasure, the

minister stressed that students will still study a native language as a subject in primary, junior secondary and senior secondary school.

“We’re proud of our languages,” he added.

The clarification follows the Federal Government’s November 2025 decision to scrap the policy that mandated indigenous languages as the main medium of instruction — a move that drew criticism from educators and cultural groups.

Educationist Anthony Otaigbe described the decision as “a step backwards for Nigeria’s education system,” arguing that it removed one of the most progressive elements of the national education framework.

In January 2026, the Bible Society of Nigeria also urged the government to reconsider, warning that some Nigerian languages had already gone extinct due to lack of active use.

Responding to these concerns, Alausa said the problem was not the policy itself, but how it was applied across regions.

According to him, many southern and North-Central states did not implement the policy at all, while parts of the Northwest and Northeast extended it far beyond its original scope.

“People were using their mother tongue to teach up to Primary Six and even JSS,” he said.

The policy, he explained, was originally designed to apply only from Primary One to Primary Three, after which instruction should switch to English.

The challenge, Alausa said, is what happens when students eventually face national assessments.

“These kids… will have to do national exams — NECO, WAEC, JAMB — conducted in English,” he said.

With limited instructional materials in indigenous languages, many students struggled to transition, leaving them disadvantaged at exam level.

“And as minister, we will not allow that to continue,” he added.

Data from the ministry, Alausa said, showed that regions where the policy was over-implemented were lagging behind in literacy and numeracy compared to others.

For students navigating Nigeria’s education system today, the shift highlights a familiar reality: while language preserves identity, English still determines access — to exams, certificates, and higher education.

The bigger question now may be how Nigeria can protect its languages without leaving students unprepared for the system they must succeed in.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.