The year is 1962 and Algeria has just won its independence from France. Abdelmajid is a young Algerian boy with warm brown eyes, who has witnessed first hand the crimes of France against his family, his neighbors and his countrymen. In 132 years of French colonization, more than 5 million Algerians have lost their lives. But despite the struggles and violence that he faced during the French occupation, he remains hopeful for future life in a free Algeria.

In the years following Algeria’s post-independence, Abdelmajid’s primary school teacher would tell him that there would be no school lessons that day. Instead, he and his peers were to go out to Hamam Al-Salaheen (the old Roman bathhouses), and instructed to plant new seedlings. Abdelmajid was overcome with joy when the teacher placed the tiny, innocent tree in his hands and had him submerge it into the fresh soil. His teacher excitedly told the students that these trees would one day grow to be a vast, beautiful forest and would symbolize the beauty of Algerians taking back their land from colonial masters.

Decades later, Abdelmajjid would bring his three daughters to this now rich and breathtaking forest pictured below. He would tell his daughters about this memorable day when he and hundreds of other Algerian children planted trees as a symbol of hope and of their resistance to French colonizers.

This brave young man was my father.

But of course, Algeria, which sits at the crown of the African continent, is not the only nation with a past deeply rooted in the complex web of colonisation. At the tail end of the mother country, South Africa is no stranger to the angst, political upheaval and disruption that stems from the imperialist mentality and colonial control. And while the earliest traces of colonialism began in the 1600’s, we still see the infinite wounds etched in the soil of Southern Africa, for it’s a tale that sadly, is not fiction at all.

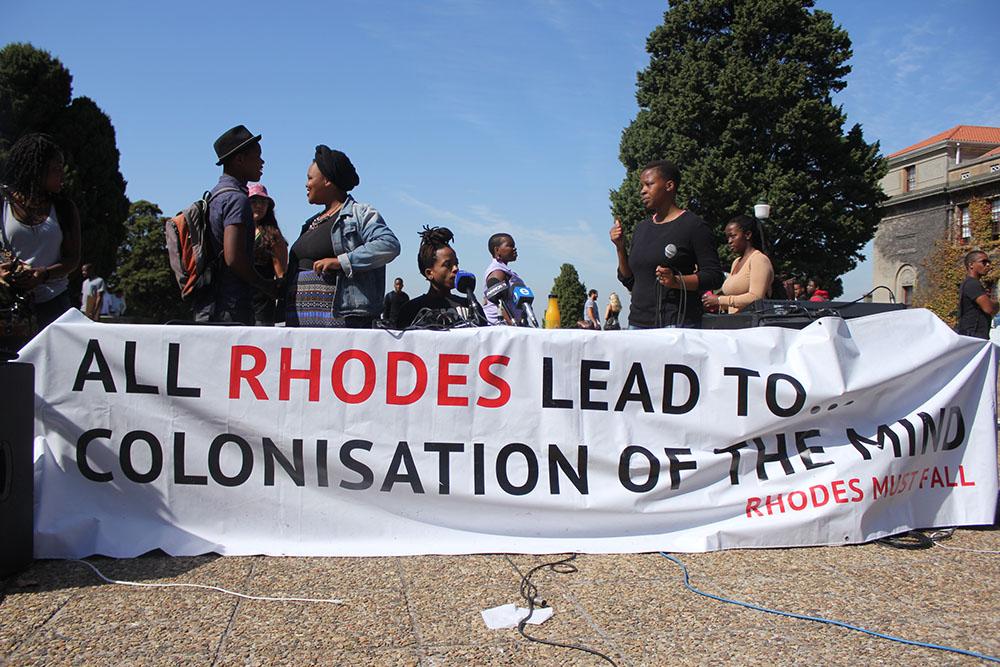

Perhaps you remember when a flurry of students stood united at the stairs of Rhodes University in Cape Town, South Africa, chanting and toyi-toying – a political protest dance – calling for the removal of the Cecil Rhodes statue, which commemorates the former Prime Minister of the Cape and controversial De Beers diamonds founder. Why did this act form such a pivotal point in modern African history, you may ask? It wasn’t because students hurled human excretions at the statue – though this became a controversial talking point amongst us all. But it made African students point to the root cause of their distress – the fact that in 2015, their education was still largely Eurocentric and did not accurately depict the struggles of their people; their ancestors.

You see, #RhodesMustFall gave African youth a means of explaining to educational leaders how it feels to be young, gifted and black – in the words of Nina Simone – and yet be unable to see yourself reflected in the very curriculum that you are forced to learn.

Now, fast forward to 2023 and we find that many who have not been affected, or their family lineage impacted by the effects of colonisation may shrug and merely suggest that ‘history is history. Have we not evolved?

And to a degree, they raise a point. The past is in fact, the past. And history remains history.

So why should we bother to try and honour the idea of decolonising current curriculum programs in African schools and universities? It’s simple. Take the 15th century slave trade, South Africa’s apartheid era, the Boer war, or Algeria’s war of independence against French colonisation. How can the future of our world – our students – learn from humanity’s past indiscretions if not presented with an accurate depiction of history in schools? In 21st century schooling, it’s ever-important that our students are learning about the version of history that did in fact occur, and not one that has been carefully curated to suit textbooks.

So where does Nigeria’s education system sit within the scale? In an attempt to follow suit with the growing trends in western education, the NTIC offers most standard subjects such as Mathematics, Sciences and English language studies. And as with many African countries, the curriculum program also offers students the chance to study their own native language; Hausa, Yoruba or Igbo. But we must also recall that prior to the introduction of Islamic and Christian education, the curriculum of the indigenous was made up of cultural traditions, legends, rituals and the passing down of knowledge to each generation from tribe to tribe. Some may argue that we have surpassed this level of education – for what good will it do our children in the real world?

And that, folks, is the whole point of the asset based approach to decolonising education. It is not enough to merely reconnect with past cultural traditions on a superficial level. Instead, we must discover ways to see the history of the nation as an asset, not a problem, nor an inconvenience. There must be respect for educational diversity. We must know where we have come from in order to understand the direction in which where we need to go.

So, in what ways can Africa as a continent take back its curriculum authority? And like the young, proud Algerian, Abdelmajid – where can we plant trees of indigenous knowledge so that the legacy of our ancestors and those who formed the pillars of our lineage, live on?

First and foremost, we must embrace, celebrate and own our diversity. Our accents. Our stories. As educators, we must let our students tell these stories and in turn, welcome those who are still in search of one. Our bookshelves need not only be lined with Shakespeare, but should be accompanied by the likes of Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche and Chinua Achebe.

The harrowing stories of history need not be swept under the rug, nor used as a form of blame. But rather, our education system must use this as a tool for the improvement of humanity.

For if not presented with an accurate depiction of the past, how will our future generations ensure that history’s most painful lesson does not repeat itself?

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.