For some time now, the way of the world has been to exclude others. Making others feel excluded while we’re part of an exclusive “club” generally makes us feel good, powerful and special. Enjoying privileges reserved only for those worthy enough to belong to this group has an appeal to the ego, that is almost irresistible. This is by no means a Nigerian thing or an African thing, it’s a human thing. Some societies have merely advanced to a level where this primordial inclination has become largely subsumed by elevating the notion of the common good. It may be worthy to note that feeling on the outside, out of the loop, that we don’t belong, or that we’re not relevant and somehow inferior, is a major cause of mental illnesses that has become so prevalent globally. The interesting thing is that by tradition, Africans have always been communal people, where everybody is included and everyone matters. We were in many ways more democratic in our style of governance and in the way we conducted our daily lives than we are now, as we continue to practice the mode of democracy foisted on us. Back then, important decisions were often taken collectively, involving all members of the community and not just a select group or a privileged few.

The African ethos of yesteryear was not too different to that of some countries of the Orient today, such as Japan and South Korea, where the interest of the society is placed before the interest of the individual. It’s no wonder the source of the adage, “it takes the village to train the child” can be found in Africa. This same disposition proved invaluable in helping the people of these Oriental countries toe the lines dictated by their leaders when it came to containing the Coronavirus outbreaks a few years back. This can be juxtaposed to the situation in the West where long held democratic ideals made it difficult for citizens to obey government directives and stem their natural urge to resist.

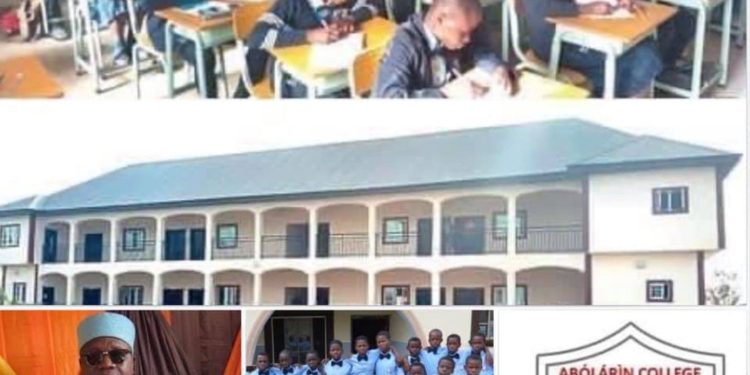

The story of The Abolarin College in the ancient town of Oke-Ila Orangun, Osun State, founded and funded by Oba Dokun Abolarin, is a truly inspiring one which epitomizes a fundamental aspect of godliness. I believe it would be helpful for us to understand that godliness goes beyond just adhering to fasts when called and attending all church programs but instead can be defined as conducting one’s life in a way in which God would readily agree, mirrors His character.

Abolarin College was established with one purpose in mind. To provide free qualitative education to indigent children, all because the man involved refuses to accept this should remain the exclusive preserve of the well-to-do. And when I say free, I really do mean free, as the school provides everything, including school uniforms, school bags, writing materials, feeding, bed linen and anything else you can think of, absolutely free for its one hundred or so pupils, and making no demand of parents, most of whom can barely keep head above water. As a further demonstration of his large heartedness and disposition to include rather than exclude, admission is not limited to his subjects only. The pupils come from all over the country. However, if the child is not conversant with the Yoruba language, he or she must learn it, in addition to English and French, because these are the languages alternately used to conduct their school assemblies. One thing I find fascinating though is Kabiyesi’s humility, uncommon in this part of the world, by regularly putting aside his royal robe and adorning the teacher’s garb, as he teaches his pupils too. Money cannot buy the invaluable lessons this simple gesture imprints on the impressionable minds of these children. To lead is to serve and ultimately, lead us to lead. This is certainly one king who recognizes the motivational power inherent in leading from the front. Reminiscent of the Japanese educational philosophy of raising leaders by inculcating this spirit of service in pupils, Kabiyesi’s pupils too must carry out daily chores for the benefit of all. For example, pupils take it in turn to help the cooks in the kitchen to prepare school meals and just as the female pupils braid each other’s hair, it is the duty of the boys to cut each other’s hair too. And before your imagination gets the better of you and you begin to wonder how squalid an environment the school premises must be because it’s free, let me put you straight. This is a beautifully built institution powered by two large generators, donated brand new by an organization which keyed into this noble vision. The children are always neatly attired in their comely uniform and all pupils are provided with their own personal computers, in addition to the provision of many other modern day facilities, required to provide a conducive environment for learning.

There are many ways in which one can define character. It can be defined as possessing the moral antenna to first seek out and to thereafter attach appropriate importance to the right values. It can also be described as having the moral strength to abide by these values even when it may not be convenient to do so. There are times when it may even be detrimental to one’s personal interest. In my opinion, character is also evident when one sees the big picture and pursues its fulfilment, placing this over and above the gratification of serving one’s personal interest. This is an attribute sacrosanct to nation building and it is one, Kabiyesi is endeavouring to inculcate in all of his pupils. What better way is there to do this than to lead by example.

I believe it was Mother Theresa who once said, “We ourselves feel that what we are doing is just a drop in the ocean. But if that drop was not in the ocean, I think the ocean would be less because of that missing drop. I do not agree with the big way of doing things.” In other words, we don’t need to wait until we’re able to perform the grandest gestures because many of us may never find ourselves empowered enough to do so. We can however do what we’re able, in our little corner. Unknown to most people, that’s indeed how the world changes; doing the little that you can and not leaving it to the other.

In a country where we have far more people living in poverty than those who don’t, that there must be many brilliant children falling through the cracks due to privation, would be a fairly safe conclusion to reach. Kabiyesi and all those led to support him, in alignment with the Japanese ethos which says “disadvantage is really seen as a collective responsibility” may never get to fully appreciate the impact their actions are having, not just in the lives of these children, but in the lives of a whole new generation. Just because they care.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.