The Proposal

Former acting chairman of Nigeria’s Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), Ibrahim Magu, believes the country’s fight against graft should start in school. Speaking in Abuja during his induction as a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Forensics and Certified Fraud Investigators of Nigeria (CIFCFIN), Magu urged education authorities to add anti-corruption studies to primary and secondary curricula. “Corruption must be fought across the board. One man cannot fight corruption. Everybody is involved, whether you like it or not,” he said.

Why He Says It Matters

Magu argues that teaching young Nigerians about ethics, accountability and forensic investigation will help change a culture where corruption is often normalized. He pointed to past difficulties—such as setting up the Nigeria Financial Intelligence Unit and explaining money-laundering laws—as proof that public understanding is crucial. Introducing these topics early, he says, could build a generation less tolerant of graft.

Role of Forensics and the Courts

Beyond classroom lessons, Magu wants stronger use of forensic evidence in Nigerian courts. He challenged CIFCFIN to work with the judiciary, schools and professional bodies to improve how fraud cases are investigated and prosecuted, noting that “if you must have a very tight case, then you have to bring in the forensic aspect.”

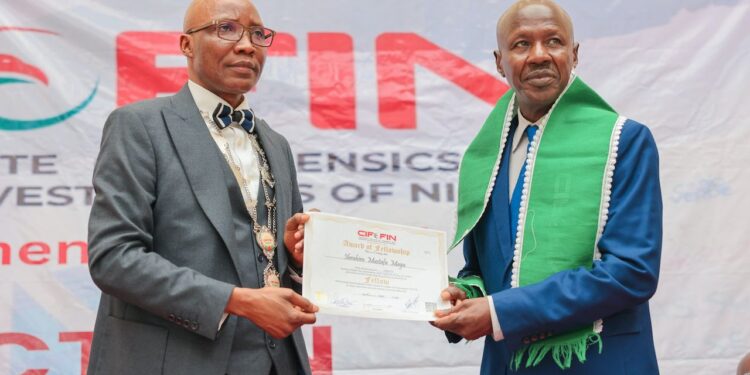

Recognition and Background

Magu’s comments came as he was honored for decades of anti-corruption work. A founding officer of the EFCC in 2003, he became acting chairman in 2015, leading investigations into the Abacha loot recovery, oil-subsidy fraud and the Halliburton bribery scandal. Now pursuing a PhD in Security and Strategic Studies, he said the fellowship “gives me encouragement to continue what we are doing, because forensic investigation is central to fighting corruption.”

The Bigger Picture

Nigeria has introduced civic and moral education before, but a dedicated anti-corruption curriculum—linking ethics with practical tools like forensic accounting—would be new. Advocates say it could complement ongoing reforms in the justice system. Critics, however, often caution that classroom instruction alone cannot fix entrenched political and institutional corruption.

Magu’s call adds weight to a growing conversation: if Nigeria wants long-term change, the classroom may be as important as the courtroom.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.