By the way, Wikipedia defines tertiary education as all formal post-secondary education, including public and private universities, monotechnics, polytechnics, colleges of education, technical training institutes, vocational schools, etc. The list appears endless but the key requirement revolves around post-secondary exposure in a formal institution. In Nigeria, for example, there are specialized institutes dedicated to training in agriculture, petroleum, trades, arts and crafts, armed forces, security forces, etc whose entry requirements revolve around secondary school certification.

Available statistics show that as at June 2023 there were 264 approved universities in Nigeria, both public and private with a larger proportion made up of private universities. Indeed, of the number, 43 were federal, 48 state-owned and the rest are private universities (some of which have not commenced operation).; 28 federal polytechnics, 43 state polytechnics, 51 private polytechnics; 23 federal colleges, 47 state colleges, 26 private colleges; among the whole lot. However, in terms of student population, public tertiary institutions account for about 90% of this while just about 10% of the students population are in private tertiary institutions.

No matter the name assigned to a tertiary institution, the challenges and problems of tertiary education in Nigeria resonate in all of them. Funding remains the Achilles Heel of many a tertiary institution in Nigeria.

It follows each one of them like five and six. And the funding gap incapacitates them in almost all areas of their core mandates, thereby limiting their quality offering. The impediments pose serious problems to key areas of the life of a tertiary institution in the country.

In this write up, two of such impediments are x-rayed and some recommendations made to overcome the devastating effects they may have on the tertiary institutions in their quest to deliver on their mandate, now and in the future.

INFRASTRUCTURAL GAP

Several authors and educationists have pointed to the lack of adequate classrooms/lecture theatres, resource rooms, staff rooms, laboratory facilities, IT facilities as major inhibitors to quality education in Nigeria. The dearth of such infrastructure such as libraries, laboratories, halls, offices, administrative blocks, hostels, road network within, water, electricity and power, hamper effective delivery of educational pursuit in Nigeria’s tertiary institutions.

The infrastructural gaps in Nigeria’s tertiary institutions at times make a mockery of the mandates of the affected institutions.

Imagine a university lacking in functional lecture theatres, sciences lacking in modern laboratory equipment, engineering without state of the art teaching aids, and lecturers without access to modern library facilities or current research works!

Observers have even tagged some universities in the country as glorified secondary schools. There are minimum infrastructural benchmarks below which a tertiary institution cannot deliver on its mandates. The regulatory agencies such as National Universities Commission (NUC), National Board for Technical Education (NBTE) try to assess the adequacy or otherwise of such facilities during resource verification exercises for new universities or introduction of new courses in existing ones. Curiously though, most of the affected institutions still scale through such exercise by the whisker. The truth of the matter however, is that most tertiary institutions in Nigeria are incapacitated by lack of the requisite infrastructure, decayed or obsolete facilities, poorly equipped laboratories and libraries, lack of access to modern research outcomes, poorly equipped staffers, lack of motivation on the part of academic staff due to a dearth of facilities and poor conditions of service resulting in part from poor funding.

The above scenario unfortunately is tied to the limited sources of funding available to tertiary institutions in Nigeria. Public tertiary institutions rely almost exclusively on government grants which figures have been dwindling due to low revenue accruable to governments who own them. Likewise, hardly do the tertiary institutions generate any meaningful IGR. Worse still, most of the publicly owned tertiary institutions are compelled to offer ‘free education’ as each student is heavily subsidized given the cost of basic items in the country today. Apart from free tuition, students and their parents/guardians are ready for a showdown whenever a publicly owned tertiary institution attempts to increase the charges on accommodation (where provided), library, medical, food (where available), etc.

The situation with the privately owned tertiary institutions is not radically different from what obtains in the public institutions as encapsulated above. Most of the private institutions manage to provide basic facilities to keep body and soul together, but hardly sufficient for the kind of quality education that is envisaged in this modern day technology driven environment. The private tertiary institutions rely heavily on the proprietary interests of the owners, the relatively high school fees payable by the students and limited IGR generated by them.

One thing is common to funding of tertiary education in Nigeria. The sources of funding are limited and highly constrained. The future of the funding template is therefore in a serious dilemma. Governments have made efforts in the past to canvass for support by introducing education tax payable by corporate bodies.

The federal government set up TETFUND many years back to offer support to publicly-owned tertiary institutions on specific aspects of their funding needs. But this remains more like a drop in the ocean. Private institutions continue to attack this arrangement for excluding them from the TETFUND initiatives.

Benchmarking Nigeria’s tertiary education with other countries, one would note a marked difference in their funding sources.

Most of the Ivy League institutions, including Harvard, IMT, were heavily supported with funds from lottery business. Some of them enjoyed and do enjoy substantial endowments from public spirited individuals.

They offer quality consulting and technical services to the corporate world, collaborate with corporate bodies in research works which fetch them substantial incomes. Such tertiary institutions also enjoy the support of their alumni associations. Tertiary institutions in developed and emerging economies charge commensurate fees for their educational offerings, devoid of sentiments and emotions.

The truth of the matter is that Nigeria’s tertiary institutions need to imbibe paradigm shifts in funding education. The various options outlined above need to be dimensioned by them. The current funding sources are limited and constrained. Public institutions need to start thinking outside the box. The economy offers limitless opportunities in the areas of industrial research. Collaborative efforts can generate humongous incomes for them. The private institutions also need to follow suit. The alumni bodies can do a lot.

As an individual, I have had the privilege of initiating support for my two universities in the corporate positions I occupied before (and the two universities awarded me distinguished alumnus status).

A student of medical college of University of Ibadan stunned the world with his uncommon support for his college/university a few years back.

These are the ways to go to overcome the embarrassing state of infrastructure in Nigeria’s tertiary institutions as we march on in this 21st Century.

EMPLOYABILITY OF GRADUATES

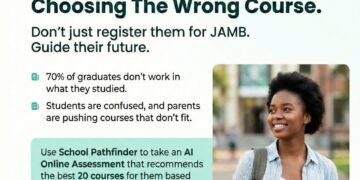

What makes graduates employable in today’s corporate world is no longer the distinctions carried in the certificate. But rather, what a graduate has to offer. And what a graduate has to offer is tied to the quality of the training he received through teaching and research while passing through a tertiary institution. This again is tied to the quality of the human and material resources at his disposal while undergoing his educational pursuit in a tertiary institution.

Unfortunately, and as captured under infrastructural deficit discussed above, tertiary institutions continue to struggle to remain afloat, amidst poor environmental conditions and training facilities.

Students are hardly exposed to the field. Lack of the requisite practical training in specific areas inhibit the employability of graduates of tertiary institutions in Nigeria. And this is again traceable to the dearth of requisite resources required for such exposure

The tertiary institutions are often accused of running with stale course contents, not in tandem with the dynamics of the current realities. The regulators often take this up to ensure the currency of learning and research in tertiary institutions in the country. For example, the National Universities Commission is at the moment reconfiguring universities syllabi and moving from the popular BMAS to CCMAS, all aimed at making the course contents more relevant and current.

Some tertiary institutions have also introduced entrepreneurship into their curricula to imbibe the culture of self-reliance on their would-be graduates. Quite a number also have as part of the normal academic programme, industrial attachments (foreign and local), exchange programmes with corporate bodies, mostly multinationals and members of the organized private sector, all with a view to deepening the quality and employability of their graduates.

In all therefore, employability of graduates of tertiary institutions in Nigeria would depend largely on how equipped they are before launching out to the labour market. And this in itself would be a function of the quality of offerings of Nigeria’s tertiary institutions.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.