South Africa’s recent efforts to reform its education system through the Basic Education Laws Amendment (BELA) Act have ignited both hope and controversy, revealing deep-rooted inequalities that continue to define access to quality education nearly three decades after apartheid.

Signed into law by President Cyril Ramaphosa in September 2024, the BELA Act aims to address systemic inequities by centralising school language and admission policies, regulating homeschooling, and enforcing compulsory education starting from Grade R. While the legislation has been praised for its bold ambition to level the playing field, it has also provoked strong opposition—particularly from Afrikaans-speaking communities who see it as a cultural threat.

Clauses 4 and 5 of the BELA Act, which give the Department of Basic Education final authority over language and admissions policies, have been the most hotly contested. Critics argue that the law could marginalize Afrikaans, currently the medium of instruction in about 10% of public schools. After a three-month consultation period, the government decided to move forward with full implementation, highlighting its commitment to inclusion over tradition.

Proponents of the act, however, frame these reforms as essential for breaking down historical barriers that have long favored privileged racial and economic groups in access to quality education. As Brand South Africa noted, the law offers a chance to promote broader inclusivity and redress educational injustice.

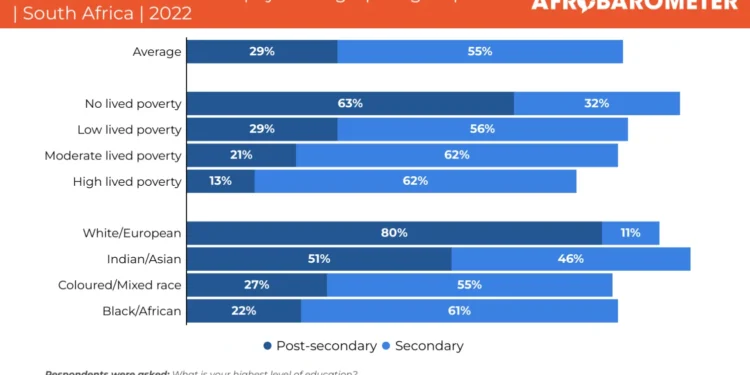

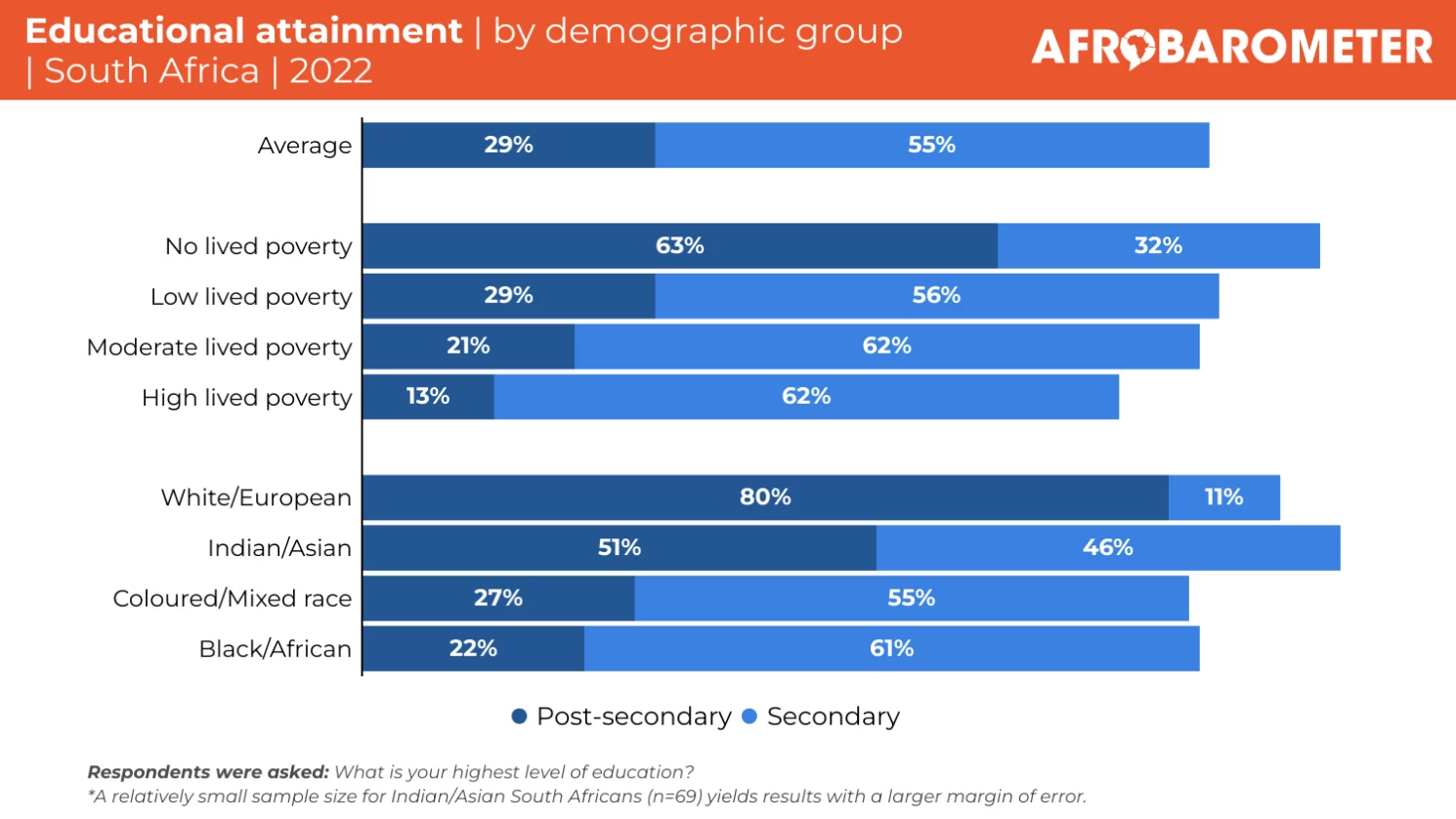

Afrobarometer’s latest findings underscore the challenges ahead. While younger South Africans generally have more education than older generations, stark disparities persist. Only 9.3% of Black South Africans hold a tertiary qualification, compared to nearly 40% of their white counterparts—a glaring gap that reflects the lingering effects of apartheid-era policies.

Economic status remains a critical determinant of educational outcomes. Citizens from wealthier households are more likely to access better education and services. Almost half of respondents identified out-of-school children as a common issue in their communities, painting a grim picture of dropout rates and access issues, particularly in under-resourced areas.

Despite these challenges, most South Africans who engaged with public schools in the previous year reported positive experiences, citing respectful treatment and ease of service. Yet corruption seeps into the system. One in ten respondents reported having to pay bribes for access—an injustice that disproportionately affects the poorest and least educated.

Public trust in government performance remains tepid. Just about half of South Africans give the government a passing grade on education—a sobering statistic given the scope of reforms being introduced.

The BELA Act represents a turning point in South Africa’s educational journey, but it also lays bare the deeply entrenched structural issues that no single policy can fully resolve. While the government’s push for a more equitable system is commendable, real progress will depend on consistent implementation, transparent governance, and sustained investment in underserved communities.

As South Africa moves forward, the challenge will be balancing reform with reconciliation—ensuring that efforts to broaden access do not alienate minority communities while prioritizing the urgent need to close the educational divide.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.