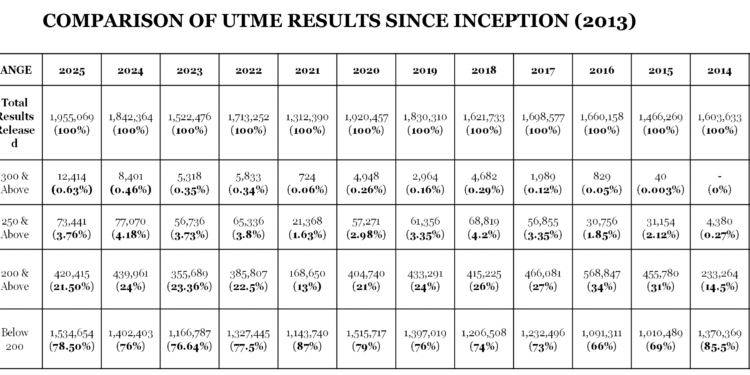

The release of this year’s UTME (Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination) results has, yet again, sparked heated debates across the country. With a significant number of candidates scoring below expectations, we must confront a pressing question: should students with low scores still seek admission into higher institutions, or should we regard these scores as a definitive statement on their academic worth?

As an educator, I am compelled to challenge the notion that UTME scores reflect the full mental capacity or potential of a student. Standardised tests such as the UTME provide, at best, a narrow snapshot of a learner’s academic preparedness. They do not account for context, and they certainly do not measure qualities such as resilience, creativity, emotional intelligence or passion—traits that often define long-term success in both academic and professional spheres.

This year’s UTME was fraught with technical disruptions, ranging from system failures to coordination lapses that disrupted exam flow. Many students reported being unable to complete their papers, while others faced prolonged delays that sapped their concentration. In such circumstances, it is deeply problematic to interpret the final score as a reliable gauge of a student’s intelligence or effort. It is even more dangerous to allow these scores to dictate a young person’s future.

Rather than allow these outcomes to demoralise students, we must encourage them to explore alternative routes to higher education. Institutions with lower cut-off marks, polytechnics, colleges of education, and remedial programmes offer legitimate and valuable opportunities to learn, grow, and prove oneself academically. These pathways should not be treated as lesser options, but rather as flexible avenues through which students can reach their goals.

We must also consider the psychological effects of our over-reliance on UTME scores. Students who perform poorly may begin to see themselves as failures, withdrawing from future academic pursuits or doubting their abilities. Meanwhile, high-scoring students may develop a false sense of superiority or neglect the development of essential life skills. Both outcomes are harmful and speak to the urgent need to adopt a more balanced and holistic approach to evaluating student potential.

Nigeria’s educational future depends on how well we nurture the talents of all students—not just those who happen to perform well on a single test. The UTME can serve as a tool for assessing readiness, but it must never become a barrier to opportunity. Admission processes must be restructured to consider multiple measures of learning and potential, particularly in a country where systemic inequality means not all students have access to the same resources and preparation.

In conclusion, a low UTME score should not be the end of the road. It should be a signpost—one that directs us to alternative paths, new strategies, and fresh possibilities. As a nation, we must stop treating standardised test results as verdicts and begin to see them as part of a much larger, more complex journey of growth and discovery.

Let us create an education system where no child is left behind simply because they did not perform well on one test.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.