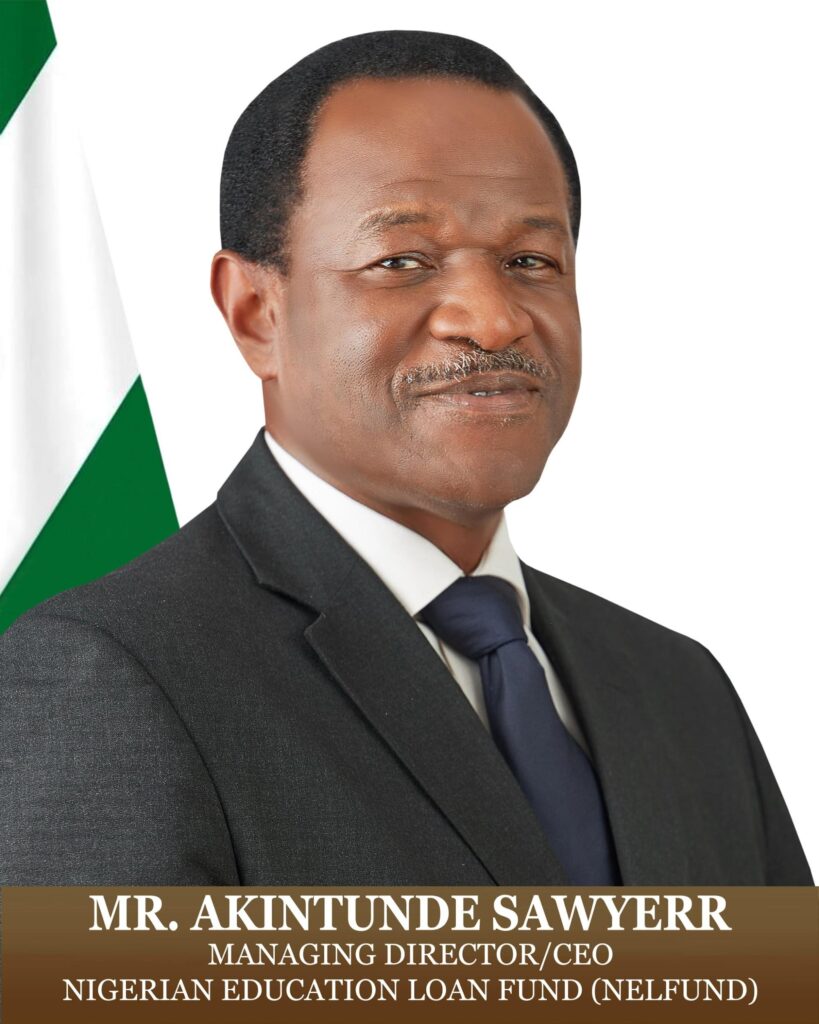

Sir, who is Akintunde Sawyerr?

I’m a patriotic Nigerian in the first instance, who genuinely loves this country. I’m a family man. I have been in the corporate world before joining the government. This is my first government position, but before now I’ve worked in the corporate world for large corporations from the UK across Germany, Denmark, Switzerland and also the Middle East. I’ve also worked and lived in the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. I have a very diverse background in healthcare, healthcare education, logistics and supply chain, medical technology, agriculture, and now the one that encompasses all of those things, education. I had most of my education in the UK, went to boarding school in the UK at the age of 12, had all my education in the UK all the way through university. I attended the University of London and here I am today back in my own country trying to contribute my quota as a recognition of what Nigeria has done for me, which is not insignificant given that all my education was paid for by my parents’ earnings from Nigeria. So it’s payback time. Payback time for me.

Is there a student loan programme of another country that NELFUND is modelled on or is NELFUND entirely unique to Nigeria? And how is NELFUND addressing equity issues to ensure inclusivity for marginalized and underserved groups, including women, rural communities, and persons with disabilities?

Well, yes and no. I think this particular student loan programme is probably very similar to the one that they have in the UK. I think that’s probably the closest scheme that this one resembles. However, this also seeks to recognise the fact that there are many people who simply cannot afford to pay for their own education or whose parents can’t afford it and therefore there’s a high number of people who drop out before they can get to the tertiary stage. They simply can’t afford it. This is unique in the sense that the loans or the law behind it, allows the loans to be given on an interest free basis. On top of that, it also does not compel the borrower to have to pay back the loan unless they’re self-employed. The obligation or repayment of the loan is on the employer who only deducts 10% of the loanee’s wages or salary to pay back to the fund. In other words, the loanee is not criminalised at any stage for not being able to pay back and also they don’t have to pay back if they don’t have a job. That is the implication of saying the employer needs to pay it back. If you don’t have an employer, you can’t pay it back. The other thing I should mention is that there is a mandatory National Youth Service Corp scheme (NYSC) that every Nigerian graduate must undertake sometime after graduation. This scheme puts no reporting obligation for payback on the loanee until two years after completion of the NYSC, which makes it even longer in terms of giving them an opportunity to find a job before they even have to think about asking their employer to pay back on their behalf.

Technology is recognised to be more efficient but has a tendency to disappoint at times. Do you have any regrets for making the entire application process technology driven and an online affair?

Absolutely none and in fact there’s no way that we would’ve been able to reach as many people in terms of the applications made if we had done this process as a manual process. We have had over 335,000 applicants and quite apart from anything else, if we set up offices to receive applications from 335,000 people, it would be a logistics nightmare, not just for us but for them because people would’ve had to travel to a location to go and complete a form and perhaps conduct an interview. So, we have no regrets because it has helped us to achieve a very high penetration rate in a relatively short space of time. The reason we’ve been able to do this is because a lot of other people have been doing a lot of great work in Nigeria, which has enabled us to leverage technology. So for example, the National Identity Management Commission (NIMC) has been collecting national identity numbers from people for years. They’ve been doing that along with biometrics and the Central Bank too has introduced the bank verification number (BVN) system that has been able to tie people to specific bank accounts. The Joint Admission Matriculation Board (JAMB) has been effectively putting in place a very robust system where people can apply to attend bonafide universities if they’ve got a JAMB number. So we’ve had the opportunity to leverage technology and of course when people register and enter an institution, they’re usually given an admission number and they end up with a matriculation number. So we’ve got a number of data points, databases that we can key into that makes it easy. We have no regrets, to your question, about using technology. It’s made things happen much quicker despite some of the challenges that people sometimes might face with technology.

There is palpable excitement that the loan will be extended to technical and vocational training. Considering the fact that TVET development is a strategic vision and direction of the Honourable Minister of Education, how soon will this happen and how will that process work?

So first of all, let me try and describe the vision to you. The vision that we have for vocational training, we are looking to see how we might be able to lift upwards of 50 million people up one level. It’s an entirely different ball game to the one we’ve been doing so far where we’re talking about maybe 1.5, 1.8 million people. Now we’re talking about what many people describe as the bottom end, the masses. How do we move them off the bottom and push them up the ladder to the next level? And the people on that level, how do we push them up to the level after that and then the level after that? There are a number of issues that we’re having to grapple with. One is based around the fact that we’re giving loans to people. We have to be able to track who they are, where they are. From an accountability perspective, we need to be able to say we gave a loan to somebody. We have some way of identifying who that somebody is. If you think about it, many of the people at the lower end of the pyramid are not as documented as people who are attending universities and polytechnics and what have you. So we intend to find ways of capturing data down to an individual level so that we have a reasonable chance of being able to account for who we gave a loan to. In other words, we want to digitalise records of people and we want to do that through engaging them through associations, clubs, cooperatives, companies, unions, communities etc. So any sort of mode of where people can convene, we want to see how we can encourage these associations to be formed if they haven’t been formed already. How they can get captured by their association. And then, it is through the association that the referral for the loan is made. That is the objective that we have. It requires us to build databases from scratch, unlike the one I just described with JAMB and others. These are people who don’t necessarily have a bank account, let alone have a phone line that can be traced from one month to the next. So our plan is to see how we can gather this data by using associations. Most people in this country belong to an association, a club, a union, a community, or have a job somewhere in a factory or in a company. And that’s how we want to work. We want to engage with these people by putting them into corporate entities so that we can track and trace. I think the other thing that we need to do and which we’re already looking at very closely is to see how we ‘certificate’ people. If you go to a university, you will come out with a BA, a BSc, an MSc, a PhD or whatever. We don’t have people coming out of vocational schools or technical training in Nigeria necessarily with a standardised document which certifies the competency level of the individual. So we will have to grapple with that as well. Otherwise helping people to get jobs becomes very difficult.

Are there plans to increase the N20K allowance to reflect the current economic realities? If yes, when? And what innovative financing mechanisms, such as public-private partnerships or impact investment, can be leveraged to expand the fund’s reach?

Well, no immediate plans and I’ll tell you why. We arrived at that figure having looked very closely at what we thought might be needed. The primary challenges for the average student in a public tertiary institution in Nigeria are their institutional fees. So the big, big, big elephant in the room is how much they’re paying the institution for their course. The N20,000 upkeep, which is an optional borrowing, is one that we believe for now is sufficient to take care of the very basic needs – photocopying, telephone calls, data, which are the sort of things that support studies and we don’t restrict how those funds are spent. But what I can tell you is that people who didn’t know how they were going to pay their school fees in the first place are immensely grateful not only to have that taken off the table, but to have a little bit extra. And by the way, N20,000, as small as it sounds, can make a big difference in the lives of some people. And these funds are paid for the entire session, which is for 12 months. So that’s N240,000 per individual. Some families have two or three children on the loan. Also, we are seeing some interesting trends for the first time. Many of these students, for the very first time, are able to give their parents some money. I was talking to a student recently who said that he was able to give his mum N5,000, his brother N5,000 and keep N10,000 for himself. To your question, do we have plans to increase it? It’s not a metric we’re chasing at the moment. What we’re chasing at the moment is how can we get as many people who need this loan to take it. Once we have maxed out on that, we’ll then start looking to see how much more comfortable it can be for individuals, and I’m sure that’s one of the things we’ll still look at.

Why do you think the student loan has received far fewer applications in southern Nigeria compared to Northern Nigeria?

Okay, so your question says why do I think so? So what I’m going to offer you is my opinion. It’s not based on any empirical evidence around why it’s happened this way. But my suspicion is that the northern part of Nigeria has suffered quite greatly from high levels of poverty that has obviously led to insurgency and perhaps banditry as well. There is a sort of need by the people in that region to find a way out of the misery that these things have caused them. And I think that they’ve recognised and seen that particularly at the institutional level. So, the institutions themselves have recognised that this is a way out for many of the people who study in those institutions and this is the same at the local communities. The institutions have been very organised about helping students apply. Conversely, in the south where there’s a greater number of mineral resources, there’s a greater number of families with members who are living or studying or working abroad and therefore there’s an opportunity for some remittances to come back home. There’s also a sense of pride in certain instances where people have this misconception that if you’re borrowing money, it’s not necessarily a good thing. And then mixing that whole borrowing issue up, without really thinking carefully about what you’re borrowing for. If you’re borrowing for education, it’s different to if you’re borrowing to buy a car unless you’re an Uber driver of course. But I think there’s a stigma in some parts of the south, attached to being a loanee. So in a nutshell, poverty levels have an effect. I think the only other thing that I want to add to that is that there are some parts of the south where there’s a high level of skepticism around anything that the government offers. This is based on historical experiences and relationships between government and people from certain corners of Nigeria. It goes back 60 years plus.

So those are my thoughts around why we’re seeing these discrepancies. It’s good to share the thoughts, but what we’re trying to do in a constructive way is to address that by making more noise in the south, putting together situations where there’s better orientation or reorientation in the south so that people take a different view and a different approach to what NELFUND is offering.

What contingency plans are in place to mitigate economic shocks that could impact funding availability or repayment rates in future?

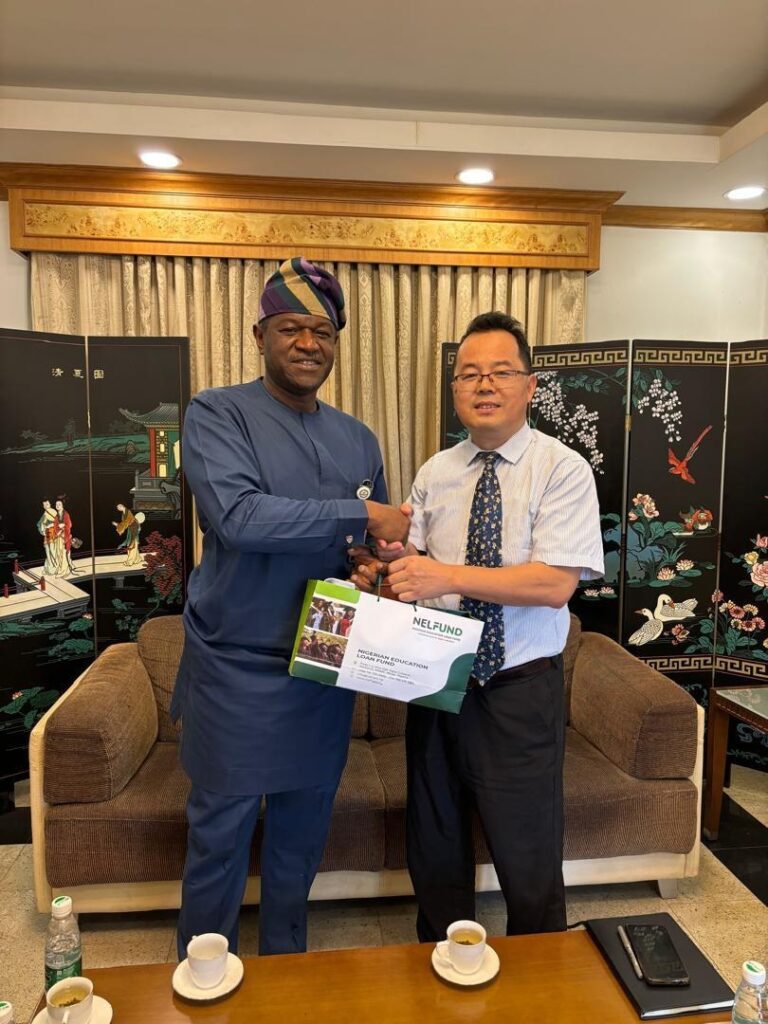

Okay, so we are currently governed by the law that ensures or enforces us to only hold funds in government instruments. Clearly one of the ways in which we can get or recognise more income is to invest more in private sector investment portfolios. One of our mitigation plans is to get some sort of waiver from his Excellency the President to allow us to be able to invest for income. The second is that we are by law allowed to receive donations. We’re allowed to receive gifts, we’re allowed to enter into financial partnerships and relationships that bolster the general reserve funds that we have. We believe that once we’re able to be active in this regard, we can actually begin to march down the road of having a more sustainable fund and a more sustainable future. We’re also going to be looking very closely about how we manage repayment of the loans so that we can maximise the return that we get on investment or on loaning out the funds, not so much investment. So these are some of the mitigants that we are looking at. We also want to set up a foundation that will allow us to look at special cases where people perhaps don’t need a loan, they just need money. I’ll give you an example. Somebody wants a loan, we give them a loan and somewhere down the line, they develop a disease or they’re involved in an accident. It means that they become disabled or physically challenged in some way. That person’s cost of learning, cost of transport, cost of everything goes up suddenly because they have lost their eyesight or lost use of their legs or arms. We want to have a fund that we can use to support such people if they’re already on the loan scheme, without us having to lend them more money in the middle of their misfortune. So we’re looking at innovative models that will allow us to do things like that. Hopefully it’s not rocket science, but we’re open to ideas if you have any.

In countries like the United State of America, student loans accumulate interest over the years while unpaid. Can Nigeria sustain an interest-free student loan? Will there be enough funds to meet the needs of every successful applicant? How will the funding of NELFUND be sustained?

I think I would turn that question round and say to you, is our current education model sustainable from a nation building perspective? And my answer to the question that I just asked, is no. Does that mean the answer to the question you asked is yes, I think possibly. I think that we have to uplift the people of Nigeria so that Nigeria itself becomes more competitive because when the people of Nigeria are doing more, they’re also more productive. They will be able to contribute more to national growth, they’ll be able to contribute more to paying taxes, they’ll be able to be more enlightened when they go into negotiations on behalf of the country and come out with better outcomes for the country. Educating your children is not a matter of choice. I think it’s an absolute necessity in the world we live in today. And you will see parents on an individual level going to all lengths to sustain this. And I think we need to have that sort of desperate attitude.

What is the biggest challenge that NELFUND has faced or is facing? And what key performance indicators (KPIs) will NELFUND use to measure its impact on access to education and socio-economic mobility? Though one is fully aware that you have been in operation for less than a year.

So your first question was about the biggest challenge we’ve faced. I think the biggest challenge we’ve faced has been trying to convince the unconvinced that this is real. That it’s not a scam, that it’s not money going into the pockets of the people who are running it. That’s been a big challenge because of the trust deficit between the government and the people. And I don’t mean this government, I mean governments over the last 60 years. It’s not uncommon though. It happens all over the world. You find many countries in the world today where people just don’t trust the government. So the big challenge for us has been to convince the people that the president means well, that his Excellency, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, means well. To convince the people that the funds are actually there and available to pay for their fees when they apply. To convince them that the system is not rigged, to convince people that it’s not a trap. It’s not like the American system where the interest compounds and people can never pay. So that whole communication piece and trying not to be misunderstood or misinterpreted has been very, very challenging for us in terms of KPIs. Numbers don’t lie. So our focus at the moment is on the numbers. How many people can we get in front of? How many people can we present our case to? How many people believe our case and how many people, having believed, decide to go forward and make an application. Those are really our KPIs. How many do we think believe us and how many actually apply? And then finally, how many can we deliver the value to in terms of the fees and in terms of the upkeep. And I’ve already shared some numbers concerning that. So those are the things we measure ourselves by today. If you ask me this question in 10 years time, I may be talking a little bit more about repayment. I may be talking a little bit more about the skills programme, which we have started. The other KPIs might be talking a little bit more around how many people took the loan and are now in the tax net? How many people who took the loan have started their own businesses? How many people who took the loan are in good jobs and earning a lot of money? The repayment, by the way, is a reflection of the employability of the people because if they’re employed then they can pay back. It’s not so much about getting the money back, which of course is important, but it’s about getting one hundred percent payback which means that a hundred percent of the people we’ve given loans to are working. It’s never going to be a hundred for a hundred. But that’s a KPI that we would look at. I think the final thing you mentioned out of that trio of questions was around socioeconomic mobility? I guess if we think about this on the basis of if you uplift everybody even by one notch – so we’re not talking about taking somebody who’s a labourer today to becoming a managing director tomorrow, that’s a complete outlier situation – but if you take a labourer and you turn them into a carpenter or you take somebody with an HND and they get a first degree, you create an upward social mobility which when done at scale, lifts the entire nation up and then you can compare the nation of yesterday to the nation of today or the nation of today with another nation with similar demographics, socioeconomic metrics. We live in a competitive world and we can probably see how that upward social mobility happens. As I say, from taxes being paid, improvement in infrastructure, how much lower you can drive the need for foreigners coming to work in Nigeria, how much you can support local manufacturing because you’ve got people who are now able to deliver to a particular quality, such that you can reduce the amount of imports or the import dependency of the nation, these are all factors that feed into the socioeconomic wellbeing and mobility I believe. (You can read the concluding part of this exclusive interview in our February issue)

___________________ Akintunde O. Sawyerr is a distinguished professional with over 35 years of diverse experience in education, private equity, logistics, healthcare, and agriculture. Born on October 6, 1964, in London, England, Sawyerr’s career has been marked by strategic insight and impactful leadership, driving growth and transformation in every role. In April 2024, Sawyerr was appointed the pioneer Managing Director/CEO of the Nigerian Education Loan Fund (NELFUND) by the President of Nigeria, recognizing his significant contributions to expanding access to quality education in the country. His academic journey began at Igbobi College, Lagos, followed by studies in the UK, culminating in a Bachelor’s degree in Chemistry from Royal Holloway University of London. Sawyerr’s early career involved key roles in the pharmaceutical and healthcare sectors in the UK, where he worked with leading companies like Glaxo, Novartis, and Boehringer Ingelheim. These roles laid a strong foundation for his future leadership across various industries. His transition to the logistics industry in 2006 saw him excel as Head of Supply Chain for London at DHL Exel Supply Chain, managing significant revenues and later leading DHL’s operations in the Middle East, North Africa, and Turkey. In addition to his corporate success, Sawyerr co-founded several ventures, including ALTS Education in 2010, which provides educational guidance to Nigerian students, and AFGEAN, the largest fresh produce cooperative in Nigeria, empowering over 2,000 farmers. His role as Partner and Commercial Director at Anaesthesia & Critical Care Consultants (A3C) further demonstrated his commitment to healthcare access in Nigeria, particularly during the COVID-19 crisis. Sawyerr is also a sought-after advisor, providing insights to international organizations such as the European Union and the Rwanda Development Board. A published author and frequent speaker at global forums, his expertise spans marketing, sales, and supply chain management. Beyond his professional achievements, Sawyerr is a devoted family man, actively involved in several prestigious clubs, and passionate about continuous learning and philanthropy, particularly in education and healthcare. His career and personal life reflect a deep commitment to excellence and service, making him a transformative leader in every field he engages with. NELFUND Student Loan Application Portal www.nelf.gov.ng

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.