These last few years have taught us a lot about isolation and separation. Millions of us have felt the pain of bereavement, the loneliness of quarantine, the sad irritation of working and learning remotely. Sharing meals and celebrations in person is so much sweeter now. We savor the joy when we include others — and when others include us.

We understand better now that social inclusion is a basic human need that can only be met by lowering the barriers that isolate and divide us.

So let’s start. Jan. 24 is the International Day of Education, when the world highlights the greatest known instrument for social inclusion — a good education, which can put any child on a path to a fulfilling life. What better way to mark the day than to begin widening the circle of inclusion to benefit one of the most marginalized populations in the world — people with intellectual disabilities.

Children with intellectual disabilities routinely encounter ostracism and bullying. They grow up apart and unequal, their gifts and abilities rejected, their vast potential thwarted. Social isolation, stigma and shame are the norm. Those who endure the prejudice understand it all too well, but an alarming number of people without disabilities fail to see it — a problem researchers call the disability perception gap. This helps to explain how, while many countries have made significant strides to meet the needs of children with intellectual disabilities, many others have not taken even the first steps. And no nation has come close to true and full inclusion.

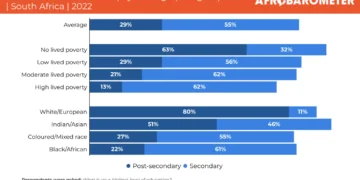

More than 85 percent of those who are primary-age and out of school have never gone to school at all. Only about 40 percent of low- and middle-income countries have education budgets for children with disabilities. And as children languish, countries pay an economic price: According to The World Bank, excluding people with disabilities from educational and other opportunities may lower a country’s GDP by 3 percent to 7 percent — a particularly heavy burden on nations in the Global South.

But here is the good news. Educators and scholars have learned how to make inclusion real. Their insights into child development and behavior show that it’s possible to build mindsets that value the potential of every student.

To help build truly inclusive classrooms and communities the world over, Special Olympics is convening a Global Leadership Coalition for Inclusion, funded by a grant from the Stavros Niarchos Foundation. This alliance of government leaders will develop an agenda of inclusive strategies in education and child welfare and push for the policies and money to make inclusion happen.

One proven way to do this is a ground-breaking, evidence-based Special Olympics program called Unified Champion Schools. In thousands of schools in 152 countries, students who don’t have intellectual disabilities learn from those who do, and vice versa. These young people take the lead in creating welcoming social norms, as sports teammates, club members and participants in a wide range of school activities.

In these schools, we have seen a spirit of inclusion take root, offering a welcome alternative to the usual schoolyard culture of cliquey isolation and casual cruelty. The new norms are infused throughout the wider community, with peers inspiring peers to think and act in a better way — with inclusive minds. Unified sports and activities allow classmates to see one another as capable and gifted — as friends and equals. A good teacher can tell you this. But a good teammate can prove it. Children who learn to play together can learn, grow, and ultimately live together.

Unified Champion Schools reap a cascade of benefits. In Mexico, Brazil, Jamaica, India, Thailand, Rwanda and Mongolia, schools have improved student grades and teacher confidence. In Greece, students without intellectual disabilities were more than nine times more likely to say they could learn from people who are different from them. In India and Kenya, more than 90 percent of students without intellectual disabilities reported a mindset more accepting of those with differences.

Unified Champion Schools are not the only path to social inclusion. But the model is tested, effective and ready to use. For the global community, always ready to talk but often slow to act, they are a way to finally get serious about a commitment to justice.

According to the United Nations, most member countries of the Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities are not on track to ensure an “inclusive and equitable quality education” for all by 2030. At a recent education summit, UN Secretary-General António Guterres urged countries to increase spending on education to 15 percent, from 5 percent.

That’s a magnificent goal. But let’s also keep sight of the need to make inclusion for people with intellectual disabilities a top global priority.

As people with intellectual disabilities constitute approximately 3 percent of the population, Special Olympics is calling on all governments to allocate at least 3 percent of their education funding to high-quality, evidenced-based inclusionary practices that fully integrate students with intellectual disabilities into their school communities. Full inclusion in education requires a commitment to social inclusion — turning isolated students into teammates, partners, allies, friends. Mere physical inclusion is not enough.

___________________________

By Timothy P. Shriver | www.euronews.com

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.