The recent scandal surrounding a Nigerian student and the forged JAMB examination results has no doubt sparked much controversy and rattled the cage of African education. It leaves much room for pondering where we as a collective group of educators and leaders stand in the age of rapidly advancing and ever-changing AI. More importantly, it begs us to question whether ethics and morale have packed their bags, fleeing in search of an easier conquest as students find new ways to dodge the red tape. Sadly, such antics are a cry for better teaching of ethics and morale to our younger generations.

Many have queried whether our students are sufficiently equipped to handle the overwhelmingly diverse points of accessibility that AI and technology offer. How can they discern what is acceptable and what is deemed academic malpractice? But we pose a different question.

Are our teachers prepared to deal with the ever-changing ethical dilemmas surrounding 21st century education?

Ball and Wilson (1994) said it best: teaching is both a knowledge endeavour and a moral enterprise. Contrary to popular belief (we’re looking at you, mainstream media), teachers are not merely facilitators of curriculum in a 9-5 job. As the late Mr Leonard Moore, former South African principal, once vividly stated, the noble profession of teaching extends far beyond the classroom. Teachers are educators of life itself. We can’t separate the intellectual from the moral, because both are in themselves intertwined.

Let’s rewind. In 19th century education, ethics was deemed of utmost importance. Right and wrong were shown by means of corporal punishment – perhaps this is the type of education you remember. By the 20th century, we moved towards other forms of behaviour management, in most cases, still opting for that ‘good student’ vs ‘bad student’ behaviourist ideology. But ethics is deeper than simply labeling what is right and wrong, and perhaps this oversight is a contributing factor as to why our students may fall victim to the blurred lines presented by AI and technology.

They see it as an ease of access – much like Google or a friend who has so willingly given tips for an assignment. And lest we forget, while our students may be 21st century citizens, they still need to be taught the essentials of 21st century learning skills. After all, integrity is the foundation of creativity and leadership.

The opportunities that technology affords us are seemingly boundless – unparalleled. We’re in the age of algorithm genius. But we’re also in the midst of a critical crossroads in education. With the fast – and necessary – move towards flexible online learning environments, digital resources and emergence of AI, this has forced our educators to ‘get with the program’, or risk wearing the unfavourable title of ‘irrelevant’. As we enter this crossroads, now more than ever it is crucial that educators understand the depths of the moral and ethical dimensions of education, for this is the very root of education at its core.

In our time as educators, we’ve learned that ethics extends itself far beyond matters of behaviour and decision making – both of which still maintain significance in matters of ethical principles. Ethics starts with the individual, first and foremost. We have the power to influence the ways in which our students think, act and respond to everyday life scenarios. Our influence cannot be underestimated, for as we teach, we project the condition of our soul onto our students, as Parker Palmer so eloquently theorises.

So, in the wake of the digital age, how well prepared are our teachers to rise to the challenge? Can they reframe and reestablish the notion of ethics with their tech-savvy students? And how are our educators continually mentored to ensure the maintenance of these ethical standards? Is it simply assumed that teachers must, themselves, be of high morale, and therefore must automatically know how to deal with the ever-changing world of education without any additional support? And where is Nigeria placed in comparison to surrounding teacher education programs around the globe in preparing its educators?

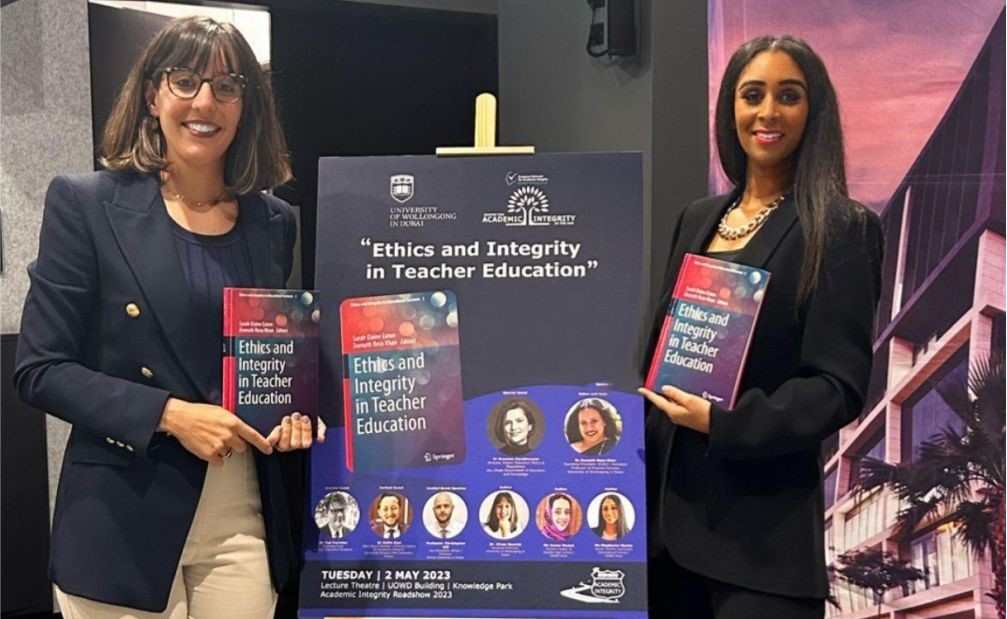

Our recent research published in Springer’s Ethics and Integrity in Teacher Education examined the gaps in teacher education programs in two leading countries, Australia and Singapore. Our findings? While mentioned in policies, ethics education doesn’t seem to find its way to the top of the priority list in tertiary institutions. Alarmingly, out of 89 Australian universities, a mere 14 universities actually offered ethics-related courses to students. While in Singapore, one of the highest performing school systems, teacher candidates are required to undertake a Professional Practice and Inquiry which aims to prepare prospective teachers for the ethical realms of education. However, our findings show that Singaporean curriculum programs lacked any further mentoring during career stages for teachers in relation to embedding ethics and integrity. So where does Nigeria sit on this scale?

While teacher education in Nigeria is not standardized, all teachers are held accountable and expected to follow the Nigerian Code of Conduct, a positive starting point for teacher education programs. The COC asks that its educators “serve as role models for learners”, and while this highlights an important aspect of teacher duty, the question remains as to whether we expect teachers to model ethics and integrity for their students without preparing them to engage in this practice themselves through consistent professional development.

Just as we train educators on the best pedagogical practices, we must also guide them on how to best teach the dimensions of ethics and integrity to their students. This cannot be reduced to a once-off university subject that becomes long forgotten when teachers are in the trenches of their career. It’s a challenging task, but not an impossible one.

Lastly, we must ponder whether we as a society are placing too great an importance on high results in standardized testing. Is this resulting in students acting out of fear rather than logic and causing severe neglect of all morale altogether in the hopes of being labelled a high achiever? And how can we assist our teachers so that they feel prepared, supported and capable of navigating through this tricky ethical puzzle?

Our tips on how to best support teachers in matters of ethics education:

Provide teachers with the time and space to reflect on their own beliefs and practice. Do staff have a sound understanding of what it means to be a moral educator in the digital age?

Training, training, training! Allow your teachers to plan lessons which embed ethics & integrity expectations. Even better – make links to curriculum subjects so students find relevance in their learning and everyday life.

University programs: Ethics need not only be a stand-alone course, but rather the ethics and integrity should be embedded at various points throughout the program

Teachers need to be provided with the opportunity to read, understand, and reflect on the Nigerian Code of Conduct – and more than once in their career.

A review and revision of the current Nigerian Teacher Code of Conduct to include AI ethics and integrity can best support educators, policymakers and students

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.

EduTimes Africa, a product of Education Times Africa, is a magazine publication that aims to lend its support to close the yawning gap in Africa's educational development.

Relevant conversation

That is so true! Thanks

Thank you madam. This is Oladapo Akande, the Editor in Chief of EduTimes Africa. Thank you for reading our publication and for reaching out a couple of times now.

I applaud you for all that you do in the education space. Can I interest you in writing an article or two for us please? You can reach out to me directly at oladapo.akande@edutimes-webapp-wordpress.hdhimq.easypanel.host or on 08056157012. I look forward to hearing from you soon.